Coastal erosion and coastal floods

Protecting New Orleans may fail, but so do more deltas around the world

December 1, 2024

Photo: The Lower Ninth Ward, New Orleans, after the Katrina flood

New Orleans as an example for the Netherlands

“The delta of the Mississippi is sometimes compared to the delta of the Rhine and Meuse in the Netherlands. The location of New Orleans, on the coast and surrounded by lakes and rivers, would then be comparable to the location of Rotterdam. There are analogies: both urban areas are built on soft, subsiding soils, while climate change is causing sea levels to rise and river discharges to increase. There are also differences: hurricanes are the main factor determining the risk of flooding in New Orleans. For protection against flooding due to storm surges during hurricanes, the dikes are designed for a category 3 hurricane. These occur on average once every more than 30 years in the New Orleans area.”

This text is a quote from a 2004 report of the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) in which the Dutch flood protection policy was evaluated for the first time since the 1953 flood disaster. I was the project leader of this evaluation. I still remember why I wrote this text in the report. I was amazed at the huge difference in safety between two comparable cities, New Orleans and Rotterdam. I wanted to place Dutch policy in an international perspective and New Orleans was a logical choice. I also wanted to emphasize how vulnerable a city like Rotterdam can become if you do not continue to take flood protection seriously, because I suspected that things could go wrong for New Orleans with such a low protection level. A year later, Hurricane Katrina flooded the city. The rest is history.

The Netherlands as an example for New Orleans

In 2006, Jed Horne wrote his impressive book 'Breach of Faith – Hurricane Katrina and the near death of a great American City'. He described the horrors of the New Orleans flood. He also wrote from an international perspective. Where I looked at the situation in Louisiana from the Netherlands’ perspective two years earlier, he looked at the Netherlands from the perspective of Louisiana. And while I was surprised by the great vulnerability of New Orleans, he praised the Netherlands as 'The world's finest flood defense'. Similar urban areas and yet a world of difference.

Protecting New Orleans will fail

Louisiana’s response to Hurricane Katrina is a Coastal Master Plan of coastal restoration, land creation and retreat. This plan will fail, according to a writer of a guest essay in The New York Times on 30 November 2024. “It will not stop the coast from receding. It will fail to create enough land to offset the acres that continue to slough into the sea. And it will fail to guarantee New Orleans’s long-term survival. The genius of the master plan is that, by building and restoring marshland, levees and barrier islands, it will fail more slowly”. The author refers to a study a few years ago that led the authors to conclude “that the disintegration of the coastal marsh had already crossed an irreversible tipping point and New Orleans, in the best-case scenario, would one day be an island in the Gulf of Mexico, some 30 miles off the coast”.

That study showed that the marshland in coastal Louisiana is more vulnerable to sea level rise than previous studies suggested. At rates of relative sea level rise exceeding 6 to 9 mm per year, marsh conversion into open water is projected to occur in about 50 years.

Critical range of sea level rise

The lead author of that study, Tulane University professor Torbjörn Törnqvist, is an expert with Dutch roots. He was a fellow student of my Physical Geography studies at Utrecht University 40 years ago. I remained loyal to the Dutch delta; he shifted course to the Mississippi.

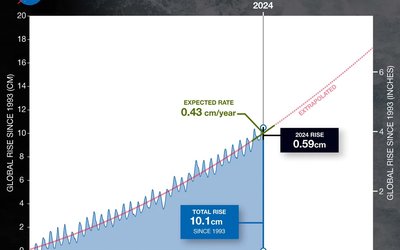

Apparently, he’s not very optimistic about the long-term future of the Louisiana marshlands, and the city of New Orleans. Remarkably, his critical range of sea level rise of 6 to 9 mm per year corresponds very well with the results of a study I conducted in close collaboration with the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL). In this study on the Geography of Future Coastal Water Challenges, we took the results from geological studies that showed that most deltas around the world were formed when sea level rise slowed down after the last ice age to 5-10 mm per year. We wondered: "What if the past is a key to the future?” Will deltas around the world start to drown once the rate of sea level rise reaches this critical range again? Current rate of sea level rise is already 4.5 mm/year, and this rate is accelerating by 1 mm/year every decade.

Not just sea level rise

Deltas are probably more vulnerable than this critical range of 5-10 mm per year suggests. In addition to sea level rise, there are other threats. Firstly, many deltas are subsiding, mainly due to groundwater abstraction. Second, dams in many rivers trap sediments that no longer reach the deltas. It is estimated that more than half of the sediment load in rivers worldwide is trapped behind dams. Third, sand mining and dredging activities extract a lot of sand from the lower reaches, which are already short of sediment due to the dams upstream. While relative sea level rise – the combination of absolute sea level rise and land subsidence – has already reached the critical range of 5-10 mm per year, we are depriving many deltas of the opportunity to grow along with sea level rise by trapping sediments upstream with dams and removing sediments in the downstream reaches.

Concerns are justified

In many studies on the future of deltas, marshlands and tidal flats, the authors draw conclusions about the rate of sea level rise at which these areas are at risk of drowning, and often that rate is in the range of 5 to 10 mm per year. The results of our studies fit in seamlessly with the results of Torbjörn Törnqvist and his colleagues for coastal Louisiana. I share their concerns about coastal Louisiana and the concerns of many scientists working in other deltas and coastal areas around the world.

The Dutch will not leave

The Dutch are lucky to live in a delta protected by ‘The world’s finest flood defense’. While elsewhere in the world people living in deltas and low-lying coastal areas are rightly concerned about their future, this seems to be much less the case for the Dutch. The Dutch will not leave their delta. As I wrote in 2007 at the end of my book about the water history of the Netherlands: “We entered this marshland never to leave again.”