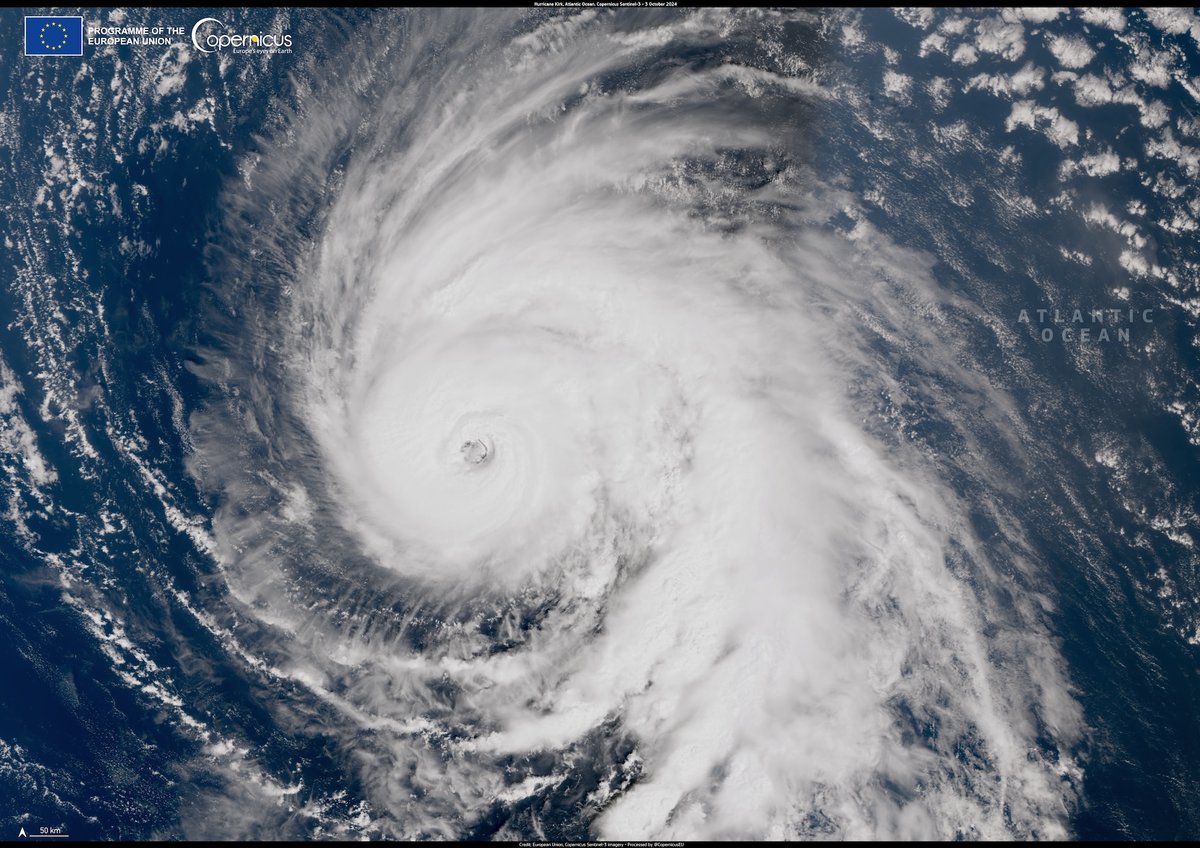

Hurricane Kirk on 3 October 2024. Credit: European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-3 imagery

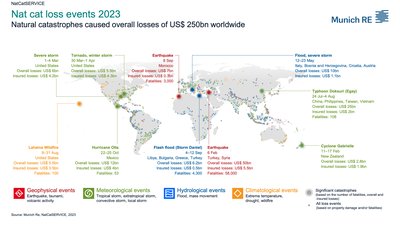

Hurricane Kirk is coming to Europe. Well, not quite. What started off as a hurricane over the Atlantic is about to hit the European continent as a storm. The hurricane will have dissipated much of its energy by then. What’s left for the projected track across northern Europe is stormy weather and lots of rain. The storm itself will probably not be that extreme. What’s making this phenomenon interesting is the fact that a former hurricane is heading towards Europe right after its origin.

Hurricane Ophelia, 2017

The scenario of a hurricane heading towards Europe without having lost most of its strength, is highly unusual. However, it does fit in the projected impacts of global warming. In fact, Dutch scientists already published a paper in 2013 entitled ‘More hurricanes to hit Western Europe due to global warming’. And 4 years later they almost saw their prediction come true when hurricane Ophelia reached Ireland just after the hurricane had weakened enough that it was no longer a hurricane.

Warming oceans

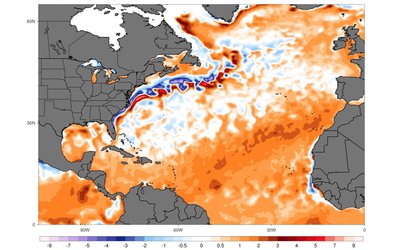

One of the conditions needed for tropical cyclones – or hurricanes – to form is that the top layer of ocean water must be at least 27°C, which is the case in the tropical waters of the western Atlantic Ocean in summer. The tropical cyclones that develop there move in a north-westerly direction, often making landfall in the United States after a few days, then continue to travel northward until westerly winds carry them over the northern Atlantic towards Europe. By the time they reach European territory, though, they are generally so severely weakened that they no longer cause any serious damage. All their strength has dissipated. But the warming oceans could change that.

Hurricane conditions stretch eastward

As the Earth warms so do its oceans, and the part of the Atlantic Ocean where water temperatures reach 27°C will stretch eastward . As a result, it is expected that tropical cyclones will also start forming closer to Europe and will not have to travel as far before making landfall there. You might accordingly expect that they will then also maintain much of their energy by the time they do land in Europe. So whereas such cyclones have posed very little risk for Europe historically, that might not be true in the future. Hurricane Ophelia may be a harbinger of changing circumstances, though it was an ‘ex-hurricane’ by the time it reached Ireland. Never before had a tropical storm of that magnitude formed that far east over the Atlantic Ocean. When it struck the Irish coast, it still had much of its ferocious strength.

A matter of time

Tropical cyclones do not occur in Europe — for now, that is. Indeed, Ophelia had just lost that title shortly before reaching Ireland. Meanwhile, the chance of a tropical cyclone reaching Europe appears to be increasing. Since the 1970s, the speed at which the onset of a storm over the Atlantic Ocean develops into a cyclone has increased. Moreover, the season in which these cyclones can form is becoming longer and longer. With an increasingly longer season in which hurricanes develop more and more rapidly, the question is not if but when Ophelia will be succeeded by a full-fledged cyclone.

Sources:

Baatsen et al., 2015. Severe Autumn storms in future Western Europe with a warmer Atlantic Ocean. Climate Dynamics 45: 949–964.

Garner, 2023. Observed increases in North Atlantic tropical cyclone peak intensification rates. Nature Scientific Reports 13: 16299.

Guisado-Pintado and Jackson, 2018. Multi-scale variability of storm Ophelia 2017: The importance of synchronised environmental variables in coastal impact. Science of the Total Environment 630: 287–301.

Haarsma et al., 2013. More hurricanes to hit Western Europe due to global warming. Geophysical Research Letters 40: 1783–1788.

Patricola et al., 2024. The influence of climate variability and future climate change on Atlantic hurricane season length. Geophysical Research Letters 51, e2023GL107881.